With poetic experimentation of today so out-of-the-box, Luke Levi is a poet who seems to want to connect with everyone, as after all, we are nature. And he does that by taking us down his inner garden in his poetry collection, titled “So Fragile Are the Beautiful Things”, where we get to appreciate the littler, more important things. For us to realise that they are bigger by going deeper into the images. It appears, as accessible as his poetry is, that he wants us to find our niche in places that can be often too literal.

This article may include affiliate links. Click here to read our full Affiliate Disclosure. If you make a purchase through one of these links, we may earn a commission at no additional cost to you.

Exploring Luke Levi’s “So Fragile Are the Beautiful Things”:

So Fragile Are the Beautiful Things

Published in 2022 by Yellow Leaf Press, his second poetry collection, “So Fragile Are the Beautiful Things”, weaves together free verse—which he refers to as “other”—and haiku forms that seem to petal on the nature tapestry. He doesn’t just explore these two common forms that are popular to the Imagist, but also tanka and new ones, such as the Fibonacci. With that in mind, what is so striking about his new approaches to the crystalline?

Nature, in poetry, is known to be a “powerful” metaphor for conveying the power of nature, according to Merseyside-based writer Alan Parry. But Luke Levi’s exploration of its fragility reminds us to take a moment. Whether by sitting on the hilltops from which we can spot a deer passing, or in a poem. The first one, “A Deer This Morning”, paints a picture of a “buck” that enjoys the taste of the sun and its last trickling dewdrops.

There is already, in the first few lines, a thread of metaphors that seem to allow us to picture the otherworldly. That which leads us down a path on which we can question why the deer is licking the sun. We can absolutely recognise that “Fragile” in Levi’s title proves more significant than just an adjective. The imagery somewhat alludes to a taste of the afterlife, that the buck’s innocence is too pure for the world we live in.

He, the I and Us

His theme of spirituality is, of course, placed into beautiful question as “fragility” and “beauty” may not prove parallel, even when they are. The deer will eventually pass, whereas the sun will remain hung—just without its dewdrops. It very well explains Luke Levi’s ethos of escaping a “sometimes-stressful” environment, yet to an extent. To forget, yet not be forgetful. Themes of desire seem to be interwoven with the concept of spirit here, because the buck seems to act as a metaphor for self, trying to taste something out of reach.

Luke Levi’s exploration of fragility seems to act as an almost-metonym for melancholy. This is since the elements in Levi’s poetry are an insertion of self. The last dewdrops communicate that the speaker can only find a fleeting moment of peace as morning opens its eyes. And the deer seems to impossibly lick that in a means of protection, for the day to come. Levi, of course, writing mostly from the southwest—Texas Country Hill—only adds to the assumption of his famous lyrical “I” acting as a very soulful example.

Haiku

Throughout Luke Levi’s “So Fragile Are the Beautiful Things”, we see a repetition of bees in his haikus that seem to develop anthropomorphic qualities, one of which is said to be “floating into summer”, while others are “drunk on spring” and “humming to a flower”. Already, the subject of one’s identity being projected onto the metaphors is enlightened as the behaviour of the bees becomes aligned with human behaviours. It seems to highlight a tone deafness, coexisting with a beautiful sadness. This is what makes Levi’s poetry distinctive, especially when you connect one to the next. And another after that.

On page forty-one, the sun is mentioned again in a captivating haiku in which the masculine body’s mission is to become coequal with a redbud leaf. He tells of the sun drinking its dewdrops. His own syllabic structure—three / four / five—of the haiku makes it look as though the sun is in control of the poem, and as well, somewhat induces rhythmic worry in us readers. The sun is, of course, separate from other nature or life, so it seems he has cleverly done this to illustrate the sun somewhat coveting the leaf’s energy.

Luke Levi’s slithery structure, of course, would make us worry for the leaf. It almost resurrects the poet’s assumed ethos to forget but not be forgetful, but to not forget the past in this sense. We all know that the female fought for their freedom, and Levi seems to imply that the male poet—or artist—would not exist without the poetess. Look at the Pre-Raphaelites!

Luke Levi’s relaxed approach to creating the haiku gives nature its own paintbrush and palette. Maybe that’s because, as we are gone, the flowers will still bloom on and beyond our graves. It makes sense that Levi’s message of fragility is one which is personal. And shows that, no matter who is reading, we seem to linger beneath the layers of a poem, whether we crafted it or not. It is no doubt why students of literature research the artwork of those who were centuries before us.

The poet’s exploration of spirit is thus confused yet innocent in its own manner. It seems to be referring to almost everything; most significantly, the feminine, the supernatural and that of colour and liveliness.

Tanka

As an experimental poet, identifying the type of poem in his collection can be quite the minefield, as most—if not all—poems stretch away from the traditional structures of what “should” be. The tanka on page eight seems to be a metaphorical imperative for the dead.

Extracting the first, second and final lines, “carry the sun / in your pocket / when the light falls apart” beautifully presents the sun with its own spirit, and funnily, shows that the sun can be controlled when light is absent. It introduces the concept of humans and the power of their creativity. A scholar, Kathleen Ratto, in 1971 mentioned in a study of the moon how she and her pupils cut out objects that were mentioned in haiku, using silver wrapping paper to aid the picturing of images.

Luke Levi’s special approach to the tanka, however, places the fiery ball in a playful means, almost as though the speaker guides us all to have the sun in our hands. The verse sends a message to create your own life, to destine yourself towards happiness amid darkness. Coming away from the typical number of syllables allows Levi to send a clear message: to dream big.

These parallels communicate that, in spirit, there is a sense of direction through a course of introspection. On page twenty, there is another tanka where the moon is crafted as a metaphor for sadness and vulnerability. The poem begins with: “these are moon days”, communicating that they are speaking from the heart and the truth. It is ironic, given that the moon is said by Kathleen Ratto to be a canvas for mystery and wonderment. Levi’s approach, on the flip side, paints the celestial face as a more authentic, personal and direct figure for words.

Progressing to the Fibonacci

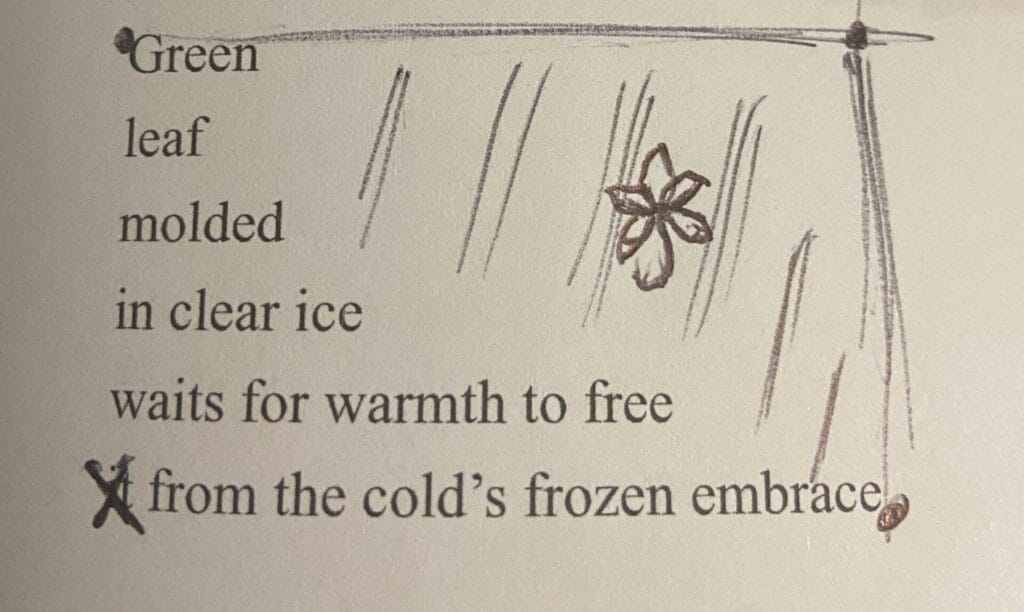

Like his other poems, Luke Levi’s approach to the Fibonacci is nuanced, in a means of observing the metaphor as one, and learning more as we read. On page one hundred and fifty-three, his Fibonacci, “Frozen Leaf” follows a similar structure of one syllable on the first and second lines, yet progresses in a way where the poem seems to control itself.

The first and final lines, “Green / it from the cold’s embrace”, seem to pair up if we were to take out “it”. Despite the leaf being trapped beneath the ice, “green” can act as a substitute for grass beyond the water. This gives the poet’s poem another layer, which he may not have initially thought about. This unique connection shows that grass can be a metaphor for safety or saviour.

It can also act as a reference to seasons, showing that spring is next after a chilly wintertime. In this case, the leaf can, too, be a metaphor for self, as it seems to represent the cliché “light at the end of the tunnel”. His confused exploration of spirit highlights that this poem possesses exactly that.

The syllabic structure: one / one / two / four, seems to show that the poet is extremely observant of the situations that surround him. It almost paints us a picture: his train of thought. Alternatives such as green show us that certain metaphors can be indirectly unpacked, leaving us with our imagination. This parallel is, as a result, one that is hidden and tranquil, as the focus is primarily on the lone leaf.

Closing with an Image

Familiar with the Imagist, poetry and photography can be a great combination, as each can convey a narrative without being descriptive. And to see the pair cross paths in Luke Levi’s collection makes this hypothesis even more true with imagination. Beautifully presented on page ninety-one, a black and white close-up of a daisy—below its haiku—allows us to enter the poet’s mind.

In the flower books, the daisy was used, and can still be used, to represent addiction, so this close-up seems to add context to what is said using no words. The haiku reads, “water droplets / kissing the daisy / spring shower”, painting a picture of renewal. Still, the close-up seems to tell us that unhealthy attachment could be all that the speaker once knew, and that the personified droplets act for change or new beginnings.

On page forty-seven, there is a haiku-accompanied photograph of vultures that descend from the clouds. The haiku has an observant tone which follows as: “three vultures / descending from clouds— / gathering for lunch”. It seems to be on the final line that makes the haiku, one which stands out in his collection. This original use of personification allows us to picture the vultures coming aligned at a dinner table. Then again, it lets us merely picture the instinct of other animals. The poet’s ability to juxtapose images of the species descending and gathering provides the poem with a fascinatingly sinister beat.

To Picture the Picturesque

As we’ve seen, Luke Levi’s new approaches to the metaphor in “So Fragile Are the Beautiful Things” are those which make us wonder elsewhere. It’s the way he is experimental with his use of syllables to be direct of what he is telling. Like before, we see an instant shift from a string of metaphors to personification, which he does by using no word that wouldn’t do much justice to the canvas. Other images—like those of the Fibonacci—seem to create a puzzle with which we can piece together something alluringly aligned. Something that darts us into another reality outside of the poem, yet in.

After all, it seems his works shoot little messages in place of an overwhelmingly large world. The way he can weave together playful themes of desire by being strategic with the types of metaphors makes his wonderfully complex exploration of spirit almost unmatchable. So, if you want to untangle a loose knot by absorbing yourself in miniature works, yet are left with many unusual ends, then this collection is one for you. Who else knew that we could carry not just the moon but the sun in our pockets?

Follow Luke Levi on social media here:

Share this article and tag us @GoodStarVibes to let us know what you make of Luke Levi’s poetry collection, “So Fragile Are the Beautiful Things”.

Have any thoughts?

Share your reaction or leave a quick response — we’d love to hear what you think!