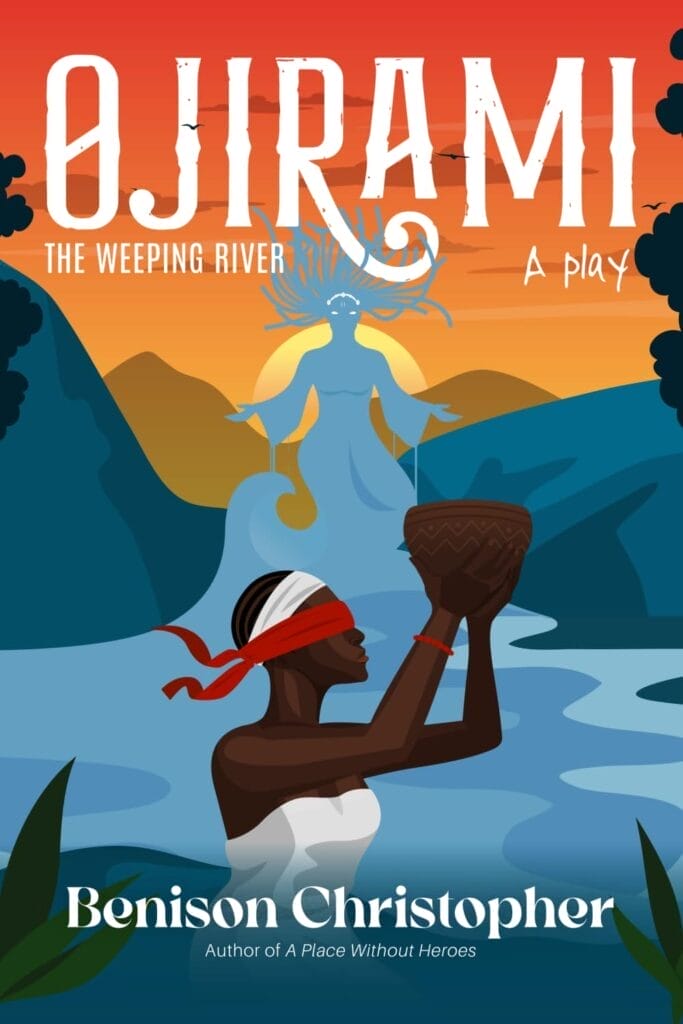

In her latest work, “Ojirami: The Weeping River”, Nigerian playwright and cultural entrepreneur Benison Christopher transforms ancestral legend into a modern stage drama that feels both urgent and timeless. Drawing inspiration from the sacred Ojirami River in Edo State, Nigeria, the play unites myth, spirituality, and human frailty in a story that confronts the consequences of ambition overshadowing reverence.

This article may include affiliate links. Click here to read our full Affiliate Disclosure. If you make a purchase through one of these links, we may earn a commission at no additional cost to you.

The opening scene immediately immerses readers in village life as Elder Afekhafe and Omomije pour libations around the community in preparation for the Ojirami Festival. Through prayer and chanting, Benison Christopher effortlessly introduces the audience to the sacred heart of the story—the village’s bond with the river and the rituals that sustain it. This introduction doesn’t just set the tone; it forges a connection between readers and the people of Ojirami, grounding the myth in tangible human experience.

At the centre of the play is Ekpen, a proud and restless young man whose ambition disturbs the delicate balance between humanity and the divine. His actions awaken a forgotten goddess—the spirit of the river itself—whose wrath becomes a reckoning for the community. In contrast, Ureshemi emerges as a quiet force of moral clarity, her composure and empathy adding depth to the story’s emotional rhythm. Together, their arcs explore pride, love, and the fragile boundary between faith and defiance.

Surrounding Ekpen and Ureshemi is an ensemble that enriches the play’s emotional and moral fabric, each figure embodying a facet of the community’s struggle between modernity and tradition. Ekpen’s parents, Eshioza and Khuyeni, serve as two opposing mirrors to their son’s conflicted heart. Eshioza, stern yet perceptive, recognises the hollowness behind Ekpen’s pursuit of prestige and his neglect of familial duty, while Khuyeni—blinded by maternal affection—clings to an idealised image of her son. Through them, Benison Christopher delicately explores generational dissonance: how parental love, when clouded by expectation or denial, can both guide and endanger.

Omomije, Ureshemi’s closest friend, stands as one of the play’s sharpest voices of reason. She sees through Ekpen’s arrogance and warns Ureshemi against mistaking charm for sincerity, embodying the wisdom of women who protect not only tradition but each other. Her presence counters Ekpen’s recklessness with grounded intuition, reflecting the strength and clarity often overlooked in tales of male ambition. It is Omomije who articulates the audience’s unspoken understanding—that Ekpen’s infatuation with Britain is not progress but escapism, a desperate attempt to outrun his own failings. He comes off extremely obnoxious, a deliberate character flaw that Benison Christopher uses to expose the emptiness of misplaced ambition and cultural disconnection.

When Oboh enters later in the play, the contrast between him and Ekpen crystallises the story’s central tension. Oboh’s humility, perseverance, and deep respect for heritage reveal a different path of migration—one rooted in gratitude rather than greed. His return home is not triumphant but redemptive, reminding both Ureshemi and the audience that success abroad means little if it comes at the cost of one’s soul. Through these layered portrayals, Benison Christopher reframes migration as a moral crossroads, showing that the journey outward is as much about integrity and remembrance as it is about distance and opportunity.

What truly stands out in “Ojirami: The Weeping River” is Benison Christopher’s characterisation. Every voice feels instinctive and distinct—so much so that readers can easily tell who is speaking without glancing at the names. The dialogue flows with natural cadence, deeply rooted in the rhythms of African oral storytelling, giving the Nigerian setting charm, colour, and heart. It’s easy to become fully invested in the characters’ words, emotions, and exchanges.

The play is structured in six acts, each containing three to five scenes, and Benison Christopher’s attention to detail in the stage directions is remarkable. Her notes provide clear guidance for stage directors while leaving room for interpretation and creativity. As a result, reading the play feels like both watching it unfold and stepping into the scenes yourself. The writing is descriptive enough to ignite the imagination, yet open enough to invite different artistic visions. This balance between precision and freedom makes “Ojirami: The Weeping River” an engaging experience on the page, not just on the stage.

At its heart, “Ojirami: The Weeping River” is a story about belonging—what it means to hold on to one’s roots while yearning for something beyond them. Ekpen’s obsession with Britain, his disdain for the customs of his homeland, and his belief that success lies elsewhere reflect a modern restlessness familiar to many who grapple with migration and identity. Through him, Benison Christopher exposes the seductive illusion of escape: the idea that fulfilment can only be found away from home. Yet the play reminds us that forgetting one’s heritage comes at a spiritual cost.

This tension between tradition and modernity is also embodied by the river itself—a living symbol of memory, continuity, and resilience. Its presence connects generations, standing as both witness and judge to human choices. When the goddess Ojirami rises, she does so not merely in anger but as a force demanding remembrance. Through her, the play asserts that heritage is not a relic of the past but an ongoing dialogue between where we come from and who we choose to become.

Ureshemi’s quiet strength and Omomije’s clarity further enrich these themes. Their voices remind us that resilience often flows from those who preserve rather than abandon their roots. In this way, “Ojirami: The Weeping River” transcends the boundaries of myth to speak directly to the diasporic experience and the universal longing to belong.

Benison Christopher’s writing balances lyrical beauty with emotional sharpness. Her language feels steeped in tradition yet rings with contemporary resonance, allowing the myth to breathe within a modern rhythm. The pacing of the dialogue, structured through acts and scenes, mirrors the ebb and flow of a river—steady yet unpredictable, moving between stillness and surge. This rhythm gives the play both emotional and spiritual dimensions, immersing the reader in its world while leaving space for reflection.

What makes the play particularly effective is how seamlessly it merges the sacred with the everyday. The myth of Ojirami is not treated as distant folklore but as an evolving truth woven into the realities of pride, migration, and human fragility. By doing so, Benison Christopher invites audiences to see myth not as fantasy but as a mirror for modern existence—a way of understanding the balance between ambition and humility, memory and progress.

Through this blend of mythic scale and personal struggle, “Ojirami: The Weeping River” achieves a kind of moral resonance that few contemporary plays manage. Its message is not merely told but felt, carried through dialogue that is rich in texture and atmosphere, leaving readers and audiences alike questioning what it means to truly honour where they come from.

Beyond the storytelling, the play speaks powerfully to larger conversations surrounding migration, resilience, and cultural heritage—themes that the author herself identifies as central to the work. These ideas ripple through the narrative, reminding us of the importance of remembering our roots, even as we move forward in an ever-changing world. It’s a reflection on the human cost of forgetting, and the sacred necessity of balance between progress and preservation.

“Ojirami: The Weeping River” shares a deep emotional resonance with Benison Christopher’s short story collection “A Place Without Heroes”, which explores ordinary people navigating extraordinary circumstances. Where “A Place Without Heroes” finds courage in everyday struggles, “Ojirami: The Weeping River” elevates those same themes through myth, showing that the challenges of modern life and the lessons of ancestral memory are intertwined.

’Ojirami: The Weeping River’ began as an ancestral tale told in whispers, and I wanted to give it new life on the page and on the stage, The story of Ekpen and the goddess is not only about a river—it is about the dangers of forgetting who we are and what we owe to our communities.

Benison Christopher

My short stories in ‘A Place Without Heroes’ carry the same spirit, proving that ordinary struggles can be as profound as myth. Whether it is a woman confronting betrayal or a man facing danger in a bank, I am drawn to how ordinary people bear extraordinary burdens. These works belong together: one rooted in myth, the other in contemporary life—both insisting on courage, reverence, and resilience.

Ultimately, this is a play that lingers. Its combination of lyrical writing, cultural depth, and spiritual reflection leaves readers thoughtful long after the final act. It encourages us to look inward—to consider our own world, our forgotten rituals, and the delicate balance we too often disturb.

A poetic and hauntingly relevant work, “Ojirami: The Weeping River” reimagines Nigerian myth for the modern world. Through its vivid storytelling and moral urgency, Benison Christopher reminds us that forgetting where we come from can have consequences far beyond ourselves.

“Ojirami: The Weeping River”, by Benison Christopher, is available to purchase in paperback format from Amazon via Black Writing Publishers.

Follow Benison Christopher on social media here:

Share this article and tag us @GoodStarVibes to let us know what you make of Benison Christopher’s book, “Ojirami: The Weeping River”.

Have any thoughts?

Share your reaction or leave a quick response — we’d love to hear what you think!